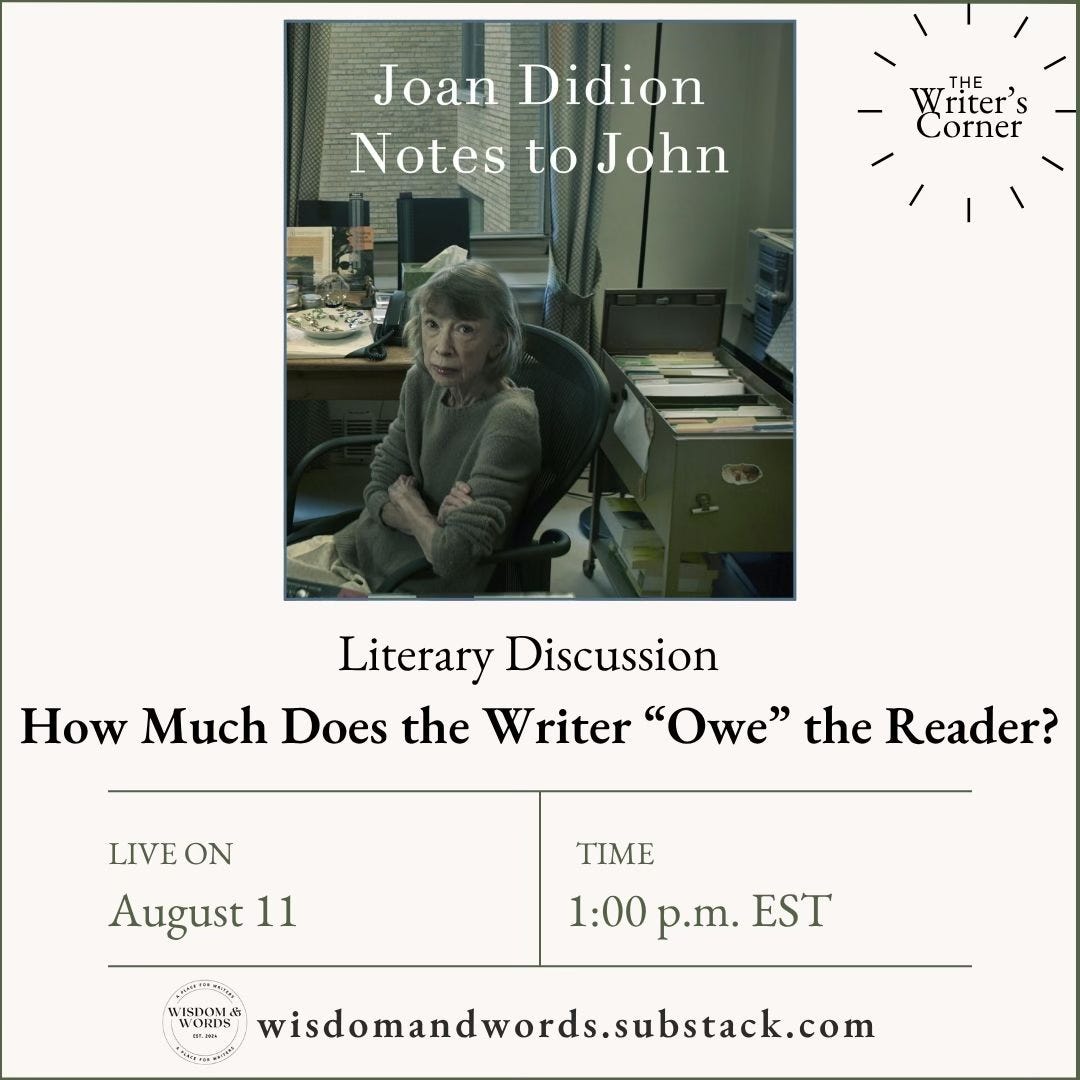

Notes from The Writer's Corner

Join us next week for A Literary Discussion: How Much Does the Writer “Owe” the Reader? Plus: What writing seeds are and why you should be collecting them.

August 11 at 1 p.m. EST/10 a.m. PST

Literary Discussion: Joan Didion’s Notes to John — How Much Does the Writer “Owe” the Reader?

This past spring, the New York Public Library opened the Didion-Dunne archive to the public. Among the materials were personal notes (addressed to Dunne) in which Didion described her sessions with a psychiatrist. These notes reveal that—like many memoirists—Didion’s published work told only part of the story.

In an article for LitHub, Evelyn McDonnell writes:

“This may be the most serious issue with the publication of this book: It confirms that Didion was not entirely honest with us. One of the reasons so many readers revere her as the master of the first-person essay is because we believe she was not afraid to tell us even the most uncomfortable of truths. Notes confirms she was hiding something from us, even if it was because she had trouble confessing it to herself. And lying damages Didion’s brand.”

Do you agree?

This Discussion will consider the following questions:

• Is publishing Notes to John an invasion of Didion’s privacy?

• When we write about our lives, do we have the right to withhold information to protect ourselves or others?

• If we leave certain details out, is that dishonest—and is some level of omission necessary in memoir writing?

• Where’s the line between “crafting” a story and telling the truth?

If you want to dig deeper on this topic …

• You can buy Notes to John here.

• You can read entries from Notes to John in this New Yorker piece.

• You can read more of the LitHub piece here.

• You can read the NY Times review of Notes to John here.

• You can read a review from The Guardian here.

Food for thought …

When writers say, “I’m blocked. I feel totally uninspired. I can’t write anything,” I often ask, “But have you really been listening?” Or, “Have you been judging ideas and tossing them aside before giving them a chance?”

Our creative brains are like muscles—the more we use them, the easier they are to access, and the more ideas come. The more space you give that side of yourself, the more it awakens. So it makes sense that when we neglect it, inspiration gets harder to find, and blocks tend to form.

One of the most important things to nurture as a writer—even when you're busy with other things—is seeds. Seeds are ideas. Tiny sparks that hit you out of nowhere. They often come when you least expect them: while walking, showering, in the middle of the night, driving, watching a movie, cooking dinner.

If you're a creative, you know what I mean—when a seed hits, it feels different. You know there’s something there.

A seed might be a sentence, a detail, a scene, a particular moment, a memory, or a line of dialogue. It could be an entirely new idea or something that fits into a piece you're already working on.

The problem with seeds is that they're easy to ignore. It's tempting to think, “I don’t need to write that down—I’ll remember it later.” But seeds are fleeting. They come and go. And spoiler alert: you probably won’t remember it later. That’s why it matters—because often, seeds are what stories grow from.

Some of the seeds you collect will take root and grow; others won’t. Your job isn’t to decide which is which. Your job is simply to gather them and see what happens. Resist the urge to assign value or judge them too quickly. Instead of analyzing what the larger piece might be, think of them as points of discovery. Each one could lead in a dozen directions—or find its place in something you’ve already begun. A seed can sit dormant for months and then, suddenly—like magic—its time has come.

Just remember: you don’t have to know where or how you’ll use a seed when it first arrives. All you need to do is collect it. Keep a “seed notebook,” jot it on the back of an envelope, send yourself a text or email—whatever works for you.