“Ma’am, are those …” the burly bearded TSA agent pauses, his eyes narrowing, “ … are those stars in your bag?”

“Those are Stars of Hope,” I start to explain, as he begins to rifle through my carefully packed bag. The wooden stars are awkward and unyielding, taking up too much space.

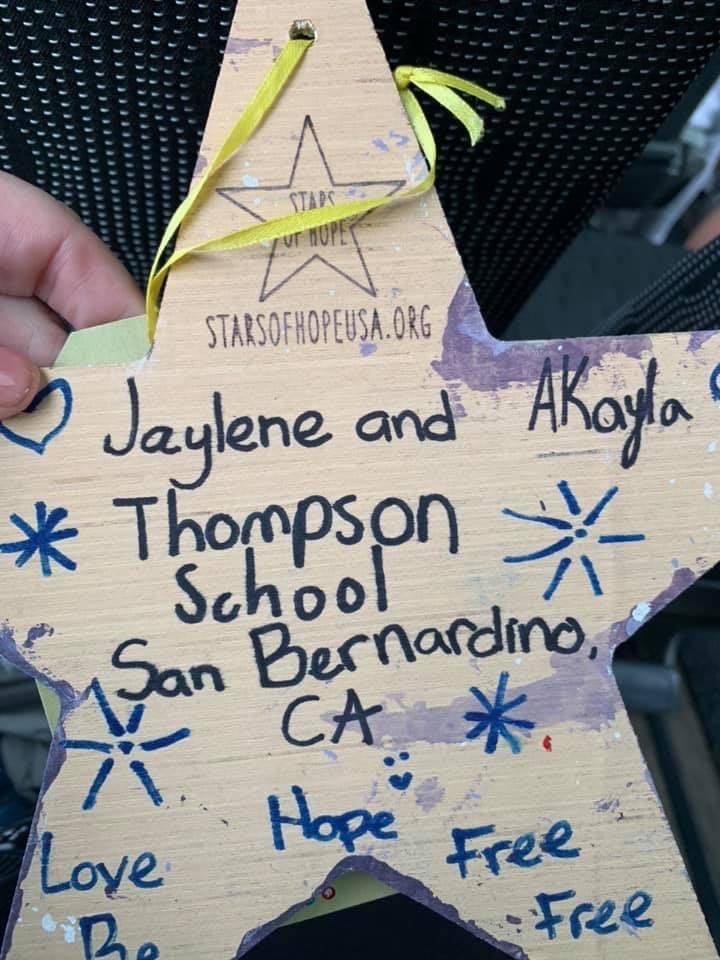

The TSA agent pulls the stars out of my bag and examines them carefully. One is splashed with red, white, blue, and yellow paint, and the other is lavender decorated with planets and stars, obviously the work of children. Both have large tags tied with a yellow ribbon that identify them: 9/11 Memorial & Museum. Stars of Hope.

When I booked this trip to France in February of 2019, I was mentally exhausted after another 50 hours spent walking the halls of Congress advocating for healthcare for 9/11 responders and survivors. My flight, as usual between Washington D.C. and St. Louis, was delayed and minutes before take-off, a former professional football player squeezed into the middle seat next to me. He and his Superbowl ring took up so much space and even more oxygen. I couldn’t move, I could barely breathe. As a non-uniformed first responder to the World Trade Center site after 9/11, I have the lungs to prove I spent eight-and-a-half months there. The small airways in them are scarred over and no longer work. Breathing in tight spaces is difficult and sometimes scary.

I finally arrived home after midnight and didn’t unpack. Instead, I started planning a trip away from the city where I live, but don’t call home; away from the last-minute calls to fly to Washington D.C. continuing what seems like an endless fight for healthcare for the permanent authorization of the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act. I decided to take a trip to France with no set schedule, no plans.

Over the next week, my trip starts to take shape—a week in Paris, a week in the country, staying in the tiny village of Morienval, a couple days in Normandy, then back to Paris. I’m booking my Paris flights when a text arrives from the 9/11 Memorial and Museum inviting me to the dedication of the 9/11 Memorial Glade, a space honoring first- responders, recovery workers, and those who have died or are suffering from health-related issues as a result of the terrorist attack.

I continue booking my flight to Paris, but now, I am routed through JFK airport in New York, with a 36-hour layover in Manhattan. I find a new hotel, one with no memories attached—a night at the Beekman, near the Brooklyn Bridge and the East River in lower Manhattan. The hotel is in a historic building, on the same site where the Mercantile Library Association once stood. I briefly consider why I’m drawn to locations layered with generations of spirits. I’ve been walking with ghosts for years now; it’s where I feel most comfortable.

On the morning of May 30th, I wander through Lower Manhattan, on my way to the 9/11 Memorial Glade, meeting up with friends, fellow responders, and survivors. These reunions are always bittersweet. So much of our time together has been mired in tragedy and loss. Many responders and survivors are sick, others are in wheelchairs, bodies broken and rebuilt; at least one will be gone within days of my return from France. We all carry scars.

I briefly consider why I’m drawn to locations layered with generations of spirits. I’ve been walking with ghosts for years now; it’s where I feel most comfortable.

When the formal ceremony ends, the crowd disperses, and my small group of friends and I walk the pathway through The Glade. Six large stone monoliths, ranging from 13 to 18 tons, inlaid with World Trade Center steel, stand at both ends of the pathway. Today the stones are altars, holding flowers, photographs, handwritten notes, and other mementos.

We linger in the sun and finally head towards the exit when a young girl comes towards us and eagerly thrusts wooden stars at us. Her friend joins her with more wooden stars. Somehow, I end up with two. I push them awkwardly into my camera bag.

I don’t think about the stars again until ten hours later, standing in front of the TSA agent as he holds them in his beefy ink-stained hands.

He reads the tag and looks at me. His eyes soften and his hands relax. He cradles the stars for a moment before stuffing them back into my camera bag.

“You take good care of these ma’am,” he says, escorting me to the front of the line without another word.

***

Waking up in Paris is magical.

I start the trip exactly as planned—with no plans. I wander through the neighborhood, stopping for freshly baked croissants at the first patisserie I encounter. Next door at a corner market, I pick up little baskets of berries and fresh flowers wrapped in pink and green paper. The second morning, I find a group of firefighters outside my hotel, and I ask them about the recent fire at the Notre Dame Cathedral. A tall dark-haired man—a captain, I think—pulls a receipt out of his pocket and scribbles an address, then invites me to visit their firehouse. I slide the receipt into my camera bag and tell them I’ll stop by.

I forget about the stars until I pack for the train to Normandy. They don’t fit anywhere. After struggling with them, I finally close the zipper and pick up the bag. The stars feel like a burden.

It’s June 11th, seventy-five years and five days since D-Day and my first visit to Normandy. The beaches, the hills, the cliffs, the fields of Normandy are full of beauty; it's hard to imagine the bloodshed that took place here until I see a bunker, covered in wildflowers; a note left by family members; a ceremony honoring an American soldier who was a teenager the last time he was here, arriving by parachute or ship. I wish I knew the rest of his story.

Later that afternoon, I walk Omaha Beach and capture photos of the spontaneous memorials that cover the sand—flowers, notes, rock cairns. As I pull out my camera, one of the stars tumbles to the ground.

Love. Hope. Free. Free.

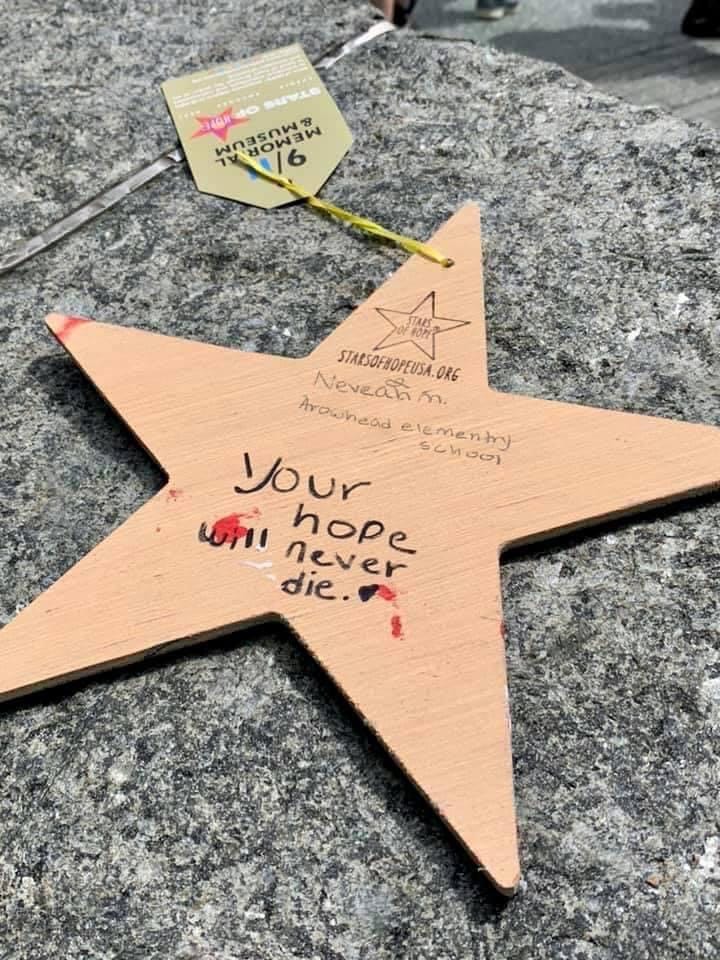

I hand him the second star and try to explain the significance. He nods and smiles a lot. He understands the 9/11 connection but I’m not sure what else. Someone in the firehouse will know. On the back of the star: Your Hope Will Never Die.

These words were painted in bright blue letters by students from Thompson School in San Bernardino, California. I move the star closer to the memorial; it becomes part of the display and part of history. I keep my camera focused on the star, the flowers, and the names. I’m reluctant to leave the ghosts lingering on the beach and clinging to the rows of white crosses. I want to know them.

On the train to Paris that evening, texts start coming in from friends at the final Congressional hearing on the Zadroga Bill in Washington DC. Retired NYPD Detective, Luis Alverez, is scheduled to speak one day before starting his 69th round of chemo. Lila Nordstrom was a high school student at Stuyvesant High School on 9/11. She has spent her entire adult life advocating for her fellow students who now live with a higher risk of cancer; at least two have already died. Lila will speak. Jon Stewart will speak.

I check into a tiny boutique hotel on Île Saint-Louis. When I finally unpack, a piece of paper drifts to the floor—it’s the receipt with the address of the firehouse given to me by the fire brigade captain on my second day in Paris. The hotel concierge gives me directions to the firehouse, just a few blocks north. All I know is that the firefighters were the first responders to the Notre Dame Cathedral fire two months earlier.

When I arrive, none of the guys I met were on duty so a young firefighter, the only English speaker in the firehouse, comes out to talk to me. I hand him the second star and try to explain the significance. He nods and smiles a lot. He understands the 9/11 connection but I’m not sure what else. Someone in the firehouse will know. On the back of the star: Your Hope Will Never Die.

It’s close to 10 p.m. when I arrive at the corner café a couple blocks from my hotel. The streets are still teeming with people. A group of Americans sitting one table over casually greet me when they hear me speak English to the waiter. As I wait for my food and wine, one of the guys tries to catch my attention. He hands me his phone and says, “You have to see this.” It’s a clip of Luis Alverez testifying to the congressional committee earlier that afternoon, followed by a clip of Jon Stewart’s testimony. While my friends from the 9/11 community were on my mind all day as I walked Omaha Beach and the American Cemetery in Collville-sur-Mer, it’s emotional to watch the testimony so far away sitting on a red and white bistro chair with a young mustachioed waiter watching over my shoulder.

Pulling out my phone, I ask the Americans if they will help me, explaining only that Lou is a friend. In 2019, I had the phone number for almost every congressional office programmed into my phone. I explain what I need from this group of Americans—call Congress. Ask, then demand, that they pass the bill. And the guys from Michigan begin calling. A couple from Los Angeles sitting nearby watch the clip and start calling. We sit at our bistro tables for several hours, making phone calls, amplifying Lou’s courageous voice, from our corner in Paris 3,328 miles away. It’s after midnight when we finish our last calls. As we say our goodbyes, the woman from Los Angeles unwinds the red and yellow scarf from around her neck—she had purchased it a few days earlier in Provence she tells me. As she wraps it around my shoulders it feels like a blessing.

Lynnette Miller is a Healthcare Advocate, Disaster Responder, Writer, and Photographer. At the peak of reaching her professional goals in a city she loves, she witnessed the first plane hit the World Trade Center on 9/11. Her memoir in progress, DANCING WITH GHOSTS contrasts her life backstage in the music industry to finding herself backstage at the World Trade Center site for nine months, and years later, advocating for sick and dying 9/11 survivors and responders. Her story sheds light on the life-long bonds that were formed during some of the most difficult days in America’s history.

This absolutely took my breath away. Such a haunting piece; a ghost in its own right. Thank you for sharing.

This is a beautiful piece, reminiscent of your unique 9/11 experience and all serendipitous events that followed . The Americans in Paris moment is most compelling, proving the true nature of the human experience, even with strangers. It also evokes memories. Each of us has a story from that day , some so very hard to carry. This piece reminds us all of the goodness of people, just when we need it the most. Thank you, Lynette, for your gorgeous words. That you, Darcey, for publishing this essay. ❤️